Shades of Gray: FEM vs. DM Risks

We know that the idea of investing in Frontier and Emerging Markets (FEM) could be unsettling for some investors.

Especially those accustomed to the structure and apparent transparency offered by financial markets in developed countries (DM).

Risks are more elevated among certain FEM nations that are in various stages of improving their economies and financial markets. More so among those with minimal chances of righting their government, economy, or financial system to the point where one would feel comfortable investing in the country.

But within carefully selected investment-worthy FEM countries, comparing the relative risks of some key elements to stability with those in highly advanced Western nations show that those select FEM nations may not be that far removed from the perceived lower-risks of the developed world.

Among the following factors, it warrants a reassessment of risk/reward thinking.

Excessive Debt

Debt in itself is not bad, as loans at the government, corporate, and personal level can help finance infrastructure projects, fuel business development, stimulate consumer consumption or investment in housing. When used smartly, debt is an investment that helps create a multiplier effect on a nation’s economic activity as opposed to a capital transfer that has no multiplier effect.

Too much debt, however, can cripple economies, companies, and individuals as the interest payments required to service the debt grow to a level that hinders growth and, at times, detracts from the ability to pay for core needs.

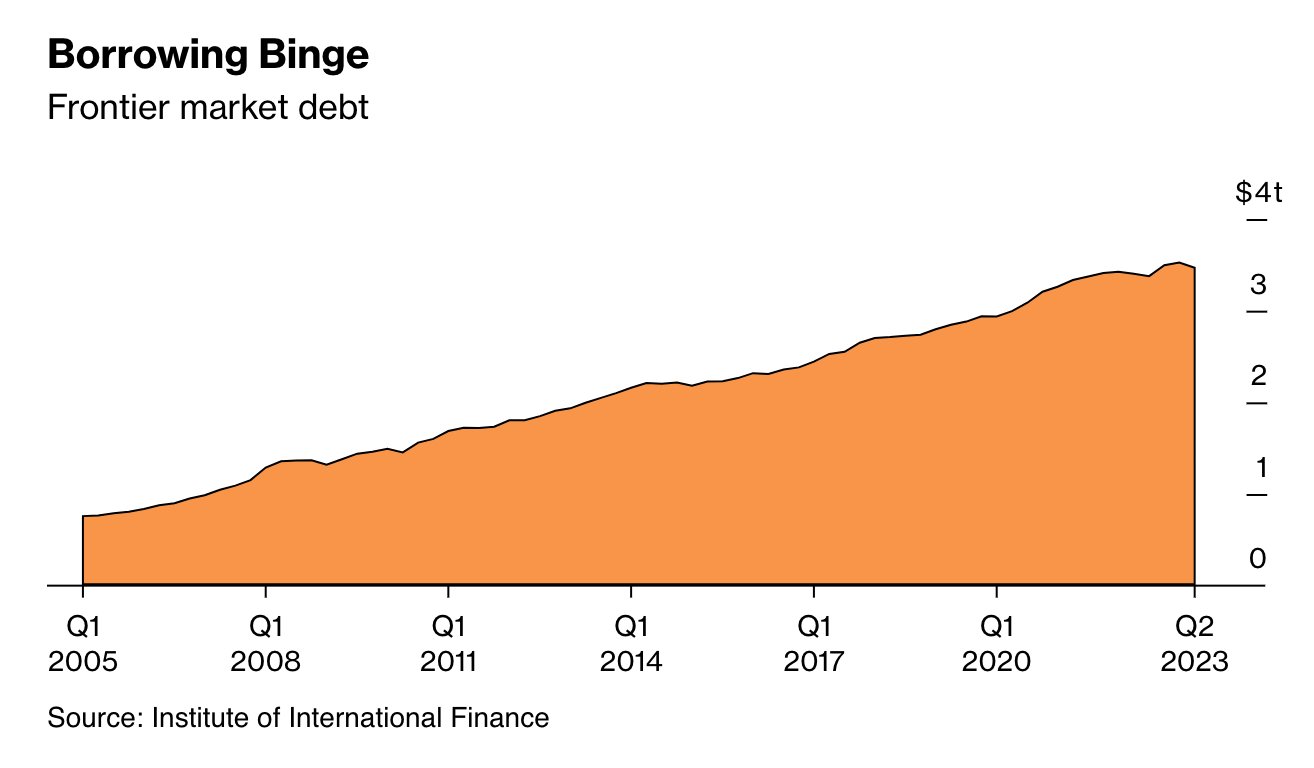

Frontier market debt levels have grown over the past two decades, with the total government, corporate, and personal debt rising more than four-fold since 2005 to around $3.5 trillion.

Furthermore, some FM nations have amassed excessive amounts of debt relative to their GDP, which further restricts spending and the ability to invest productively.

Outside of the broad brush, however, nations such as Vietnam are expected to keep government borrowing near 40% of the nation’s GDP over the next few years and Kazakhstan’s government debt-to-GDP ratio was less than 25% in mid-2023. Applying a different lens, the private debt-to-GDP ratios in mid-2023 in Vietnam was 129% and only 24% in Kazakhstan.

Figures to monitor, to be certain, but only more so is debt in developed markets.

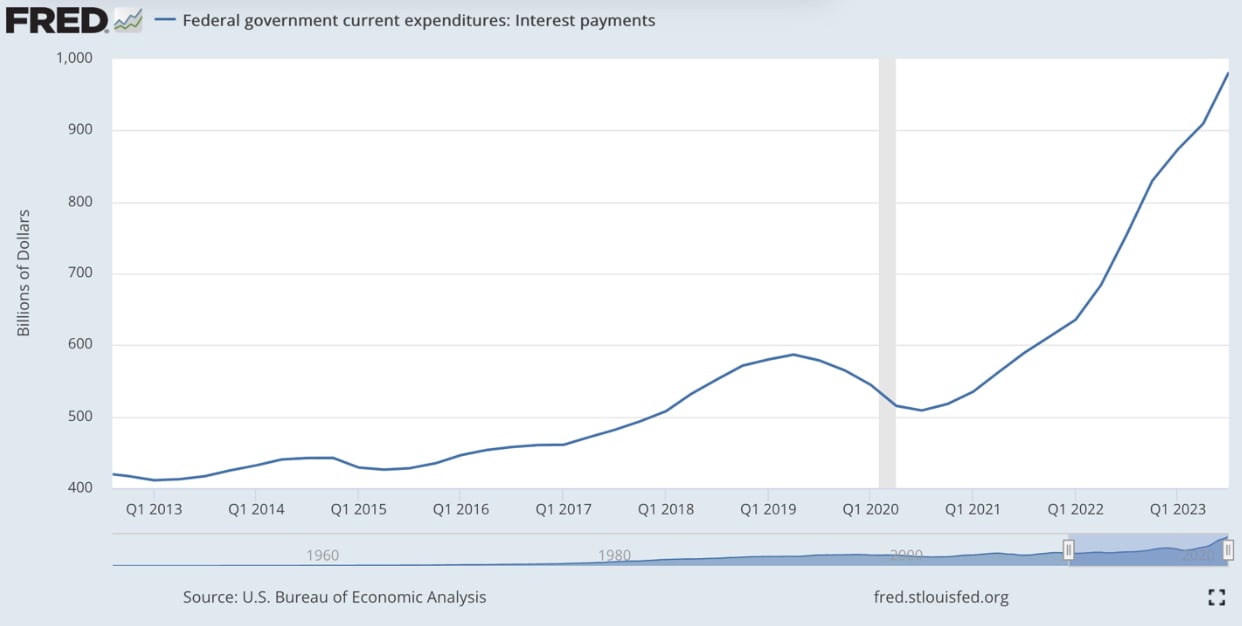

Consider that in the U.S., total public debt totaled more than $33 trillion, equaling 120% of GDP at the end of the third quarter. Additionally, the private debt-to-GDP ratio topped 150%. For the U.S. federal government alone, debt interest payments totaled more than $980 billion at the end of the third quarter—more than double its level a decade earlier.

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A091RC1Q027SBEA

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/A091RC1Q027SBEA

The equation is relatively simple: When more money must pay interest, less is available for investment in productive capacity. Whether it’s a government, corporation, or household. Plus, select FEM nations remember the lessons learned in financial crises such as the ones experienced in 1997 and 2008, and they understand they must withstand much more economic volatility than DM countries.

Systemic issues have also contributed to the availability of investor funds for FEM entities. While the International Monetary Fund and World Bank have streamlined the restructuring process, wary investors limited investments when rates were at historical lows. Having been through this many, many times, FEM nations understand the impacts high debt levels can have on growth—lessons that the DM universe currently appears set to learn the hard way.

Regulation

Another potential drag on constructive cash flows is regulations—laws and mandates for businesses and organizations.

For example, in the U.S. in 2022, the Competitive Enterprise Institute, a libertarian think tank, estimated that regulatory burdens translated into a $1.9 trillion cost to businesses. A National Association of Manufacturers study pegged the total at $3.1 trillion.

While industries such as banking and energy have long been subject to numerous regulations, especially in oil and gas, pressure is presently ramping up on technology firms. Consider the executive order signed into place by President Joe Biden in October that set standards for artificial intelligence that included responsibilities for tech firms.

Meanwhile, the European Union recently passed both the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act, which impose new regulations on most online businesses—from multinational platform operators to regional retailers.

In contrast, the vast majority of FEM nations have far less interest in setting rules and mandates for their businesses. Instead, their No. 1 priority is growing and answering the demands of their young populations for jobs.

Yes, requirements can be handed down by FEM governments, but they tend to be designed to stimulate local investment. For example, Indonesia recently ordered mining companies to not simply export iron ore, but to refine that raw material into end products, which would then be exported as higher-value finished goods.

Broadly speaking, regulations are social constructs that require time, energy and resources which countries scrambling for growth cannot afford to commit. Instead, regulations tend to be the purview of the wealthy and nations higher up in the food chain. Plus, their existence frequently introduces the need for insurance and a sense of litigiousness among consumers, producers, and governments—all of which tend to constrict growth as a result of substantial frictional costs.

Consider one of the early actions of Javier Milei after he became President of Argentina in

just last December 2023: He proposed changing or eliminating around 300 regulations that he saw as drags on the South American country, which has been struggling with high inflation and excessive debt levels. We believe the challenges in Argentina will be nearly impossible to overcome, but slashing the regulatory burden and government costs is a good start.

Political and Civil Strife and Dysfunction

Conventional DM wisdom says that less-developed nations are prone to instability due to self-interested governments that focus largely on enriching the ruling class while shirking the needs of the masses living at sub-standard levels who occasionally rise up to challenge the system.

Today’s reality, however, skims much muddier waters.

Yes, Myanmar has slipped into civil war, government officials in Sri Lanka are targeting ethnic minorities, and Bangladesh is not much of a functioning democracy anymore.

But for a nation like Vietnam, there’s no room for civil strife—it’s simply not tolerated and all levels of the population recognize it’s bad for business and jobs. Meanwhile, in countries such as Indonesia, the Philippines, and Thailand, noise and strife stemming from societal differences sporadically surfaces, but speaking out is discouraged by the ruling class. For many in those nations, they don’t have the time and money to worry about the types of things that cause civil strife.

Alternatively, consider the lingering political and civil fallout in the U.S. from the 2020 election. In Europe in early 2023, parts of the Continent ground to a halt due to strikes and protests over soaring inflation, especially energy prices. France was also hobbled by large and sometimes violent demonstrations in response to the government’s move to raise the mandatory retirement age to 64.

Specific to the political landscape in the U.S., how are the increasingly galvanized divisions between the left and right that different from those in Argentina where the election of the libertarian-minded Milei in Argentina reflected sharp political distinctions? The divide adheres to each nation’s economies and the constant flip-flop on the redistribution of wealth versus the emphasis on individuals advancing through their own efforts.

Corruption—However You Define It—Universal

Frankly, we believe some of the blurriest lines between FEM and DM risks exist in the broad concept of government corruption.

This frequently comes up in discussions about FEM investing with U.S.-based and even U.K.-based investors, and it’s a fair question to ask.

Certainly, there are FEM nations that suffer from insidious levels of corruption which create a gross misallocation of assets. For example, Bangladesh appears to be rapidly receding into a kind of autocratic, dictatorial direction with government decisions seemingly purely designed to benefit the top 10-20 families in the country. Elsewhere, corruption is thoroughly systemic in Nigeria and Egypt.

But the developed world should not be let off the hook. Bribery scandals that surfaced in late 2022 in the European Union and late 2023 in Japan reminded the world that greedy maneuvers by high-level public servants don’t always correlate with a small GDP.

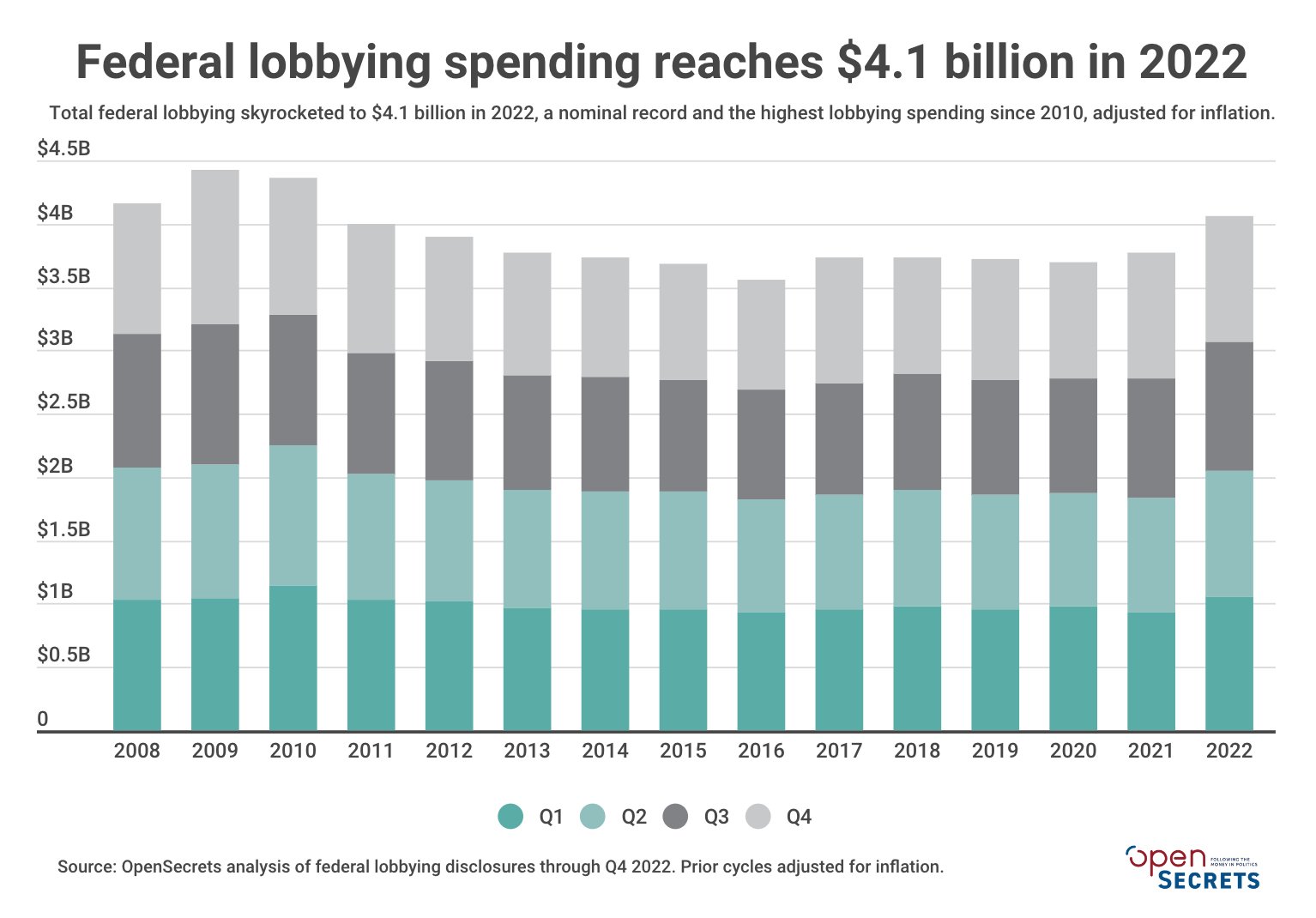

Furthermore, it’s fair to ask what defines corruption. Consider the abundance of lobbyist groups in the U.S. which solely exist to influence the decisions of elected members of Congress and the Senate. Their actions are not rooted in what’s beneficial for the country, but in the interests of the companies that pay their bills.

And the bills are excessive—a reported $4.1 billion was funneled into federal lobbyists in 2022. Companies are spending millions and millions and millions of dollars to effectively subvert enough Senators or Congressmen to protect their interests.

Source: https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2023/01/federal-lobbying-spending-reaches-4-1-billion-in-2022-the-highest-since-2010/

Source: https://www.opensecrets.org/news/2023/01/federal-lobbying-spending-reaches-4-1-billion-in-2022-the-highest-since-2010/

Essentially, corruption should be viewed as something that tilts the playing field—if everything is on an equal footing that would be an indication of no corruption. DM investors can’t be holier than thou because it’s a different type of officially sanctioned corruption which has an equally negative impact on the greater good of the country and its growth and investment.

Keeping Clear-Eyed About Risks

Admittedly, many of the perceptions of unstable FEM nations are grounded in reality as countries controlled by oligopolies of power are usually growth negative. As active FEM managers, we actively avoid investing in those countries and others with seemingly similar power dynamics.

Yet, we also believe many of the perceptions of stability in DM countries provide investors false comfort as measures designed to benefit a select few also detract from growth prospects.

We aren’t arguing that challenges and risk factors in developed markets are on par with FEM nations, but we do believe that the gray areas between the two classifications have expanded over the years, especially with regard to risks in the developed world.

In turn, we believe that risk-adjusted returns from an FEM allocation warrant a more realistic analysis relative to DM risks and potential returns.

To further explore how FEM risk factors compare to those in the DM universe, contact Consilium today or subscribe to our insights on Frontier and Emerging Markets.